- Politics & Governance

A scenario analysis of the democratic transition in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s democratic transition remains fragile. The interim government struggles to deliver reforms and prepare the country’s first credible election in 16 years, with risks ranging from orderly democratic renewal to violent breakdown.

About this report

This analysis is part of our Enterprise Intelligence suite, designed for organisations that need sustained, country-level insight. In some cases, reports may also be purchased on a one-off basis.

To discuss access for your organisation, get in touch.

As Bangladesh prepares for a historic election year, this report assesses Bangladesh’s post-2024 transition and the interim government’s capacity to deliver the first credible election in 16 years.

It maps how institutional weakness, party fragmentation and security risks intersect with external pressures from India, China, and the United States and with the Rohingya file.

After providing a profile of the key actors and political parties, this report assesses three scenarios for the February 2026 polls—an orderly democratic transition, a disputed outcome, or a security breakdown leading to emergency rule.

It sets out the key signposts, market implications, and practical choices needed to translate a volatile opening into a durable mandate, investment revival, and institutional repair.

While reforms and broad public demand for change raise hopes for stability, entrenched patronage networks, shaky geopolitical conditions, weak institutions, and elite uncertainty over whether the election will occur keep risks high.

Executive Summary

- Bangladesh prepares for its first credible election in 16 years under an opposition-backed interim led by Muhammad Yunus; a February 2026 date is announced, but uncertainty about timing persists amid a youth-heavy electorate.

- Security capacity is strained. Degraded policing meets an unprecedented deployment plan (drones, 40,000 body cameras), while administering 115 million voters across 40,000+ centres heightens rural violence risks.

- Reform remains contested. The July Charter’s 80+ measures face disputes over FPTP versus PR, legal status, and adoption pathway, slowing implementation.

- Party balance is asymmetric. The BNP is structurally advantaged; the Awami League is banned and leaderless in exile yet active through networks; Jamaat has regained registration; the Jatiya Party could inherit segments of Awami’s base; and the NCP channels youth but lacks depth.

- The economy stabilises at a lower trend. FY25 growth near 3.3% with easing inflation and stronger remittances, offset by banking fragility and tariff/LDC-graduation headwinds for garments.

- Three scenarios frame risk: orderly transition (45%), disputed outcome (20%), or security breakdown/emergency (35%) driven by distrust, dubious interim government postures, communal flashpoints, and potential loss of policing control.

- Business impacts diverge: a smooth vote compresses risk premia and restarts projects; a dispute disrupts logistics and funding; should security conditions deteriorate, we would expect intermittent shutdowns, increased risk-transfer costs, and a protracted reputational recovery.

- Regional stakes are high. India’s posture is complicated by sanctuary for Awami fugitives and Indian allegations of minority rights violations in Bangladesh; China deepens cross-party ties; the United States counters China within its Indo-Pacific strategy while cautioning Islamist actors; the Rohingya file remains volatile with chances of escalation.

- If voting proceeds credibly, BNP is positioned for a clear majority or supermajority; with Awami excluded, Jatiya Party could emerge as principal opposition, Jamaat likely third, and NCP’s gains contingent on seat-sharing.

- If BNP forms a government and executes its programme, investors gain first-mover openings in logistics, energy, export-focused manufacturing, fintech, data infrastructure, certification and skills platforms, and agri-value chains.

1. A shaky democratic transition from authoritarian rule

A year after the Monsoon Revolution, which toppled long-time Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the initial excitement is fading in Bangladesh.

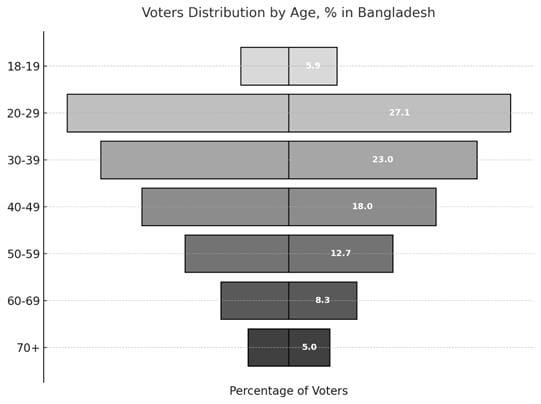

The apparently nonpartisan, opposition-backed interim government now faces the daunting task of implementing reforms and ensuring a level playing field for what would be the country’s first free and fair elections in 16 years. Gen Z and Millennials, 60% of the population and 42% of voters, have never had a chance to cast their votes in a real election—until now—and they are hungry for real reforms.

The Nobel Peace laureate CEO of this transition—Dr Muhammad Yunus—being frustrated with the infighting and a lack of consensus among the post-Hasina winning coalition, reportedly considered stepping down and drafted a resignation speech in late May. Yunus provides this interim government with much-needed credibility and legitimacy to both the domestic and international audiences.

Recognising the high stakes of such a possible falling apart, there came a breakthrough next month in June when Yunus met the hitherto exiled leader of the opposition, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)’s de facto chief, Tarique Rahman, in London.

The leaders reached a compromise, agreeing to hold the election in mid-February 2026, before Ramadan, provided sufficient progress was made on reforms and the trial of the massacre allegedly committed by the toppled regime during last year’s uprisings.

Later, on the July Uprising Anniversary on August 5th, Yunus formally declared that the election will be held in February next year.

This electoral transition aims to restore democratic institutions but faces significant challenges due to political fragmentation, unresolved questions about electoral processes, and competing visions for reform.

When Yunus took over from a bloody uprising in which, according to the UN investigations, at least 1400 people were shot dead in street protests in July-August 2024, the interim government led by him was tasked, by its own admission, with three job descriptions: trial of the massacre, reform of the broken state institutions, and a free and fair election.

Hasina’s 16-year authoritarian rule was characteristically marked by electoral controversies, e.g., even after stuffing ballot boxes, voter turnouts were as low as 20% in 2024.

Not to mention that during 2009–2024, Bangladesh was sanctioned by the US State Department for severe human rights violations, with at least 600 enforced disappearances of opposition members and 500+ killed in “encounters” or “crossfires”, as documented by the UN.

The regime was accused of undermining judicial independence and controlling the bureaucracy to suppress dissent, alongside financial crimes involving corruption and money laundering. A UN report suggests these actions may constitute “crimes against humanity” due to their systematic nature.

A white paper on the economy, submitted to Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, claims an average of $16 billion was siphoned off annually, totalling approximately $240 billion over 15 years. Hasina’s close confidante led the S. Alam Group, which alone allegedly laundered at least $10 billion through bank takeovers facilitated by a military intelligence agency, DGFI.

Yunus took over a corrupt civil-military bureaucracy full of the remnants of the ancien régime that hitherto helped Hasina become the autocrat she was. For a good week after Hasina fled to India, there was no police presence in most of the stations for fear of public backlash and violence directed against the forces for being the primary instrument of repression.

Bringing the police back to stations and training them how to do riot control while not firing live bullets was something the new government needed to learn on the go.

The uncertainty surrounding the election chiefly stems from the fear that such a weak administration might not be enough to push back against the historical use of force during elections if left unchecked.

The second source of uncertainty is that some civil-military elements within the government allegedly want to (a) prolong the tenure of either this or a reconstituted unelected government; and (b) resist the ascension to power of BNP’s de facto leader, Tarique Rahman.

The third source of uncertainty stems from geopolitical factors, specifically whether India will meddle by using fugitive, banned members of the BAL to orchestrate subversive anti-Bangladesh activities from its soil.

1.1 Electoral uncertainty and political reforms

When Sheikh Hasina fled to India last year, she left behind a constitutional vacuum. Under Hasina, elections were fixed through a disciplined, top-down machine that monopolised state violence. With that monopoly now broken and security forces weakened, the coming vote risks fragmented, inter- and intra-party violence filling the vacuum.

To preserve continuity and shield the revolutionaries, the opposition parties adopted the July Charter, yet they remain divided over its legal status, implementation, and whether the pre-July 2024 constitution should be suspended.

The National Citizen Party (NCP) and Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) argue the Charter offers little beyond the status quo, and fundamental questions persist over the choice of FPTP or proportional representation and whether the party chief can be the Prime Minister at the same time. Administrative capacity poses an added hurdle.

The bureaucracy has not run a credible election since 2008 yet must organise 115 million voters across more than 40,000 polling centres with up to 2 million workers.

The National Consensus Commission is meanwhile pursuing 166 reform proposals covering constitutional, electoral, judicial, and anti-corruption measures. A recent survey by BRAC found that 52% of the Bangladeshis want reforms.

The BNP—three-time former ruling party—rejects far-reaching changes without an electoral mandate, whereas JI and the newly formed student-led NCP demand key reforms before any vote.

These reform proposals are amalgamated in the July National Charter as a foundational roadmap for institutional reform. The Charter outlines 84 actionable reforms across constitutional governance, electoral integrity, judicial independence, anti-corruption enforcement, and public administration.

Central provisions include limiting prime ministerial tenure, introducing a bicameral legislature, enhancing caretaker government mechanisms, and restructuring the judiciary and police to curb political influence. It also proposes proportional representation and constitutional recognition of the 2024 uprising as a historical democratic movement.

While broadly backed by over 30 political parties, implementation of the charter has been delayed by disputes over legal enforceability and whether adoption should occur via referendum, parliament, or a transitional People’s Assembly.

Despite these hurdles, the Charter is a cornerstone of Bangladesh’s political transition and a key document for investors assessing future regulatory and institutional stability in the post-Hasina era.

The NCC is considering elevating the July National Charter to the status of a legally binding document, following demands from the Islamist and student-led parties (JI, NCP, and Islami Andolan) in Bangladesh.

To absolutely lock in the changes already agreed on, the commission may recommend that political parties commit to enacting a special constitutional ordinance granting the Charter supreme legal authority above all existing laws and judicial decisions.

The BNP objects to granting supra-constitutional status to the July Charter, arguing it would set a dangerous precedent by prioritising a non-constitutional document over the established legal framework.

The party also rejects the need for a constitutional assembly, asserting that the existing parliament can effectively implement necessary reforms without undermining the republic’s democratic foundation.

The BNP has offered no credible safeguards against the corruption that defined the Awami League era, coupled with allegations of rampant local-level extortion and quid pro quo deals, rekindling fears of bank looting and graft from the BAL era.

Combined with the precedent of last year’s youth-driven “monsoon revolution”, a BNP-led government—despite electoral legitimacy—could face rapid mass mobilisation, keeping overall stability risks elevated.

Part of the reason why the Yunus government struggled to leash the main political party, BNP, affiliated extortion and corruption cases is that there is a widespread perception among the administration and police that BNP will get a landslide victory in the next election, and they want to preemptively register their names in the good books of BNP.

This also means that once and if BNP do come to power after the election, only a willing and able elected government with grassroots support and legitimacy can handle it better. Although BNP’s track record during the 2001-06 era is marginally better when it comes to curbing corruption, it remains to be seen whether it can keep pace with the hunger for more from Gen Z.

Table: Where do the major parties stand regarding the reform proposals?

Against this backdrop, the NCP chief coordinator Nasiruddin Patwary declared on 12 August that the February election “will not take place”, citing stalled reforms and the slow progress in the trials of July Massacre perpetrators.

In terms of voter numbers, NCP might not be a significant party yet; however, this statement needs to be taken seriously because NCP was formed by the revolutionaries who ousted Hasina and installed the Yunus-led interim government.

His statement—issued a day after NCP leaders met U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Tracey Ann Jacobson—is perceived by many in Dhaka as external stakeholders may support a postponement of the February election. Ms. Tracey Ann also held a meeting with the National Unity Commission members, including its de facto chief, Ali Riaz, who is also a US citizen and a professor at a university in Illinois.

This development renewed the uncertainty surrounding the election even after the government’s declaration on August 5th of the February election timeline.

Even if BNP gets its much-cherished elections in February without committing firmly to reforms, while an all-opposition, 2024-style boycott is unlikely, some parties may still refuse to participate, thereby partially delegitimising the election.

In that scenario India—an adversary of the post-Hasina settlement—would gain additional avenues to mount negative PR campaigns against Dhaka in Western capitals, just as it previously lobbied on Dhaka’s behalf during controversies over human rights abuses and sham elections under Hasina. However, a recent survey by BRAC found that 70% of all Bangladeshis believe that the next election will be fair.

If the poll proceeds, significant risks remain. Under stricter scrutiny, urban voting is likely to be orderly. But in roughly 2/3rds of all constituencies that are rural, the BNP and its rebel candidates in waiting—multiple BNP contenders per seat, each wielding muscle and money, who will not get the party ticket—could exploit local power brokers and sympathetic or opportunist officials.

The government plans an unprecedented security deployment, yet these forces are compromised and suffer low morale, while BAL loyalists embedded in the administration may still sabotage the process.

Local authorities and police increasingly cooperate with BNP and, in some areas, JI, while NCP influence remains confined to a few prominent student leaders within and outside the interim government.

1.2 The political party dynamics

This section presents an overview of the political party dynamics for the upcoming election.

1.2.1 Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)

With Hasina’s Awami League pushed to the periphery—its top figures in exile and its grassroots network largely inactive—the Bangladesh Nationalist Party has risen to dominate the political landscape and is broadly perceived as the next governing party.

The BNP’s agenda focuses on democratic restoration, institutional depoliticisation, and transparent governance, aiming to correct past corruption and authoritarianism through electoral integrity, legal accountability, and administrative restructuring to ensure investor confidence and policy predictability.

The BNP promised a national unity government after the election if elected. It seeks to reset governance by rejecting the newly proposed proportional representation and committing to a reformed FPTP electoral system to avoid political fragmentation.

BNP's proposed judicial reforms include merit-based appointments and an empowered anti-corruption commission to address systemic financial misconduct, including the $200+ billion banking sector scandal. Administrative decentralisation, union-level accountability, and digital governance are central to its strategy to rebuild regulatory trust.

The BNP envisions a bicameral parliament by 2030, prime ministerial term limits, and legal safeguards against executive overreach. BNP’s proposals offer opportunities in civic tech, public service digitisation, and human rights infrastructure.

Tarique Rahman, the de facto leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the son of its founder, General Ziaur Rahman, and two-term Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, remains in exile in London.

It is widely believed that his continued absence even after the fall of the Hasina government is due to the Hasina regime’s lingering influence within the military’s top brass—who, despite recent reforms, remain largely untouched. A subset of these senior officers is allegedly strongly opposed to the prospect of a Tarique Rahman premiership.

Whether Tarique Rahman can overcome these entrenched obstacles and return to contest the upcoming election remains uncertain. However, his return appears increasingly likely, as any attempt by elements within the military to obstruct this process would likely trigger significant public backlash.

1.2.2 Bangladesh Awami League (BAL)

Operating from a discreet, high-security residence in Delhi, Sheikh Hasina—South Asia’s longest-ruling dictator—is orchestrating a calibrated bid to re-enter Bangladeshi politics.

On 31 July 2025, she convened seven senior Awami League strategists, instructing them to rebuild clandestine cells and “mobilise activists” ahead of the February 2026 polls, while parallel small-group sessions via Telegram and Zoom now relay her directives to cadres inside Bangladesh. Such calls by Hasina have real implications.

The Army’s Directorate of Military Operations disclosed on 31 July 2025 that it had taken Major Sadikul Islam Sadek into custody for allegedly training Awami League loyalists at a clandestine site near Dhaka—underscoring that Hasina’s comeback bid leans not only on political mobilisation but also on cultivating sympathetic nodes within the military.

Hasina’s network relies on encrypted messaging and diaspora fundraising but must operate under the shadow of “Operation Devil Hunt”, a nationwide manhunt that has jailed more than 11,000 loyalists and stripped the activities of the Awami League of legal status.

Even as she fights an international crimes trial in absentia carrying a possible death sentence—bolstered by leaked audio that allegedly records her “use lethal weapons” order—Hasina is betting that voter fatigue, elite fragmentation, and Indian diplomatic cover will create a narrow corridor for her return, turning Bangladesh’s democratic transition into a high-stakes contest between revolutionary legitimacy and the resilience of an ousted autocrat.

However, under the current circumstances, the chance of Hasina or BAL’s rehabilitation is extremely low. Hasina is unlikely to return without risking immediate arrest; her absence has left the party leaderless and party activity constrained to online activities and rare and sporadic small-scale processions in some rural pockets, with no legal pathway to contest the February 2026 elections.

Unless a future elected government opts for an expansive reconciliation framework—still politically toxic among revolutionaries and the public at large—the BAL appears destined to persist as an outlawed remnant abroad, its domestic machinery dismantled and its once-hegemonic role eclipsed by emerging, reform-minded coalitions committed to insulating Bangladesh’s nascent democracy from any revival of personalised authoritarianism.

1.2.3 Jamaat-e-Islami, Jatiya Party, and National Citizen Party

Following the July 2024 uprising, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) has reemerged as a significant political force, leveraging its reinstated registration (June 2025) to contest the upcoming February 2026 elections.

Its voter base, historically around 4-10% of the electorate, draws primarily from conservative Muslims, conservative urban middle-class youth, and rural government curriculum-based madrasa (Alia) communities, bolstered by its student wing, Islami Chhatra Shibir’s strong participation and leadership in the July uprisings.

JI’s post-July stance emphasises an “Islamist left” identity, blending Islamic values with social justice, anti-corruption, and inclusivity, appealing to younger voters disillusioned by the Awami League-BNP cycle. The party’s push for proportional representation (PR), constitutional reforms, and a ban on the Awami League reflects its aim to reshape Bangladesh as an Islamic welfare state.

Despite gaining traction through rallies like the August 2025 Suhrawardy Udyan event, JI’s appeal is tempered by its controversial 1971 Liberation War role, requiring careful rebranding to expand beyond its traditional base. Despite the social media hype, JI is unlikely to achieve surprising success in the scheduled February 2026 election.

The Jatiya Party (JP), an ally of BAL and led by G. M. Quader, commands an estimated 5–7 per cent of the vote, concentrated in northern Bangladesh—especially Rangpur—and among rural and urban middle-class voters.

Much of this support reflects loyalty to its founder, the late General Ershad, who directed disproportionate development projects to the region. Post-July 2024, the party has positioned itself as a moderate force, supporting early elections and a “refined” Awami League’s participation to ensure inclusive polls, while advocating for PR to enhance representation.

If Hasina gives her approval, hitherto lesser-known BAL leaders could contest the election on the Jatiya Party’s ticket, consolidating the party’s latent or residual support base of around 20% and positioning it as the main opposition in the next parliament.

The National Citizen Party (NCP), formed post-July 2024 by student leaders like Nahid Islam, targets a nascent but growing voter base, estimated at ~5%, comprising urban youth, students, and reform-minded citizens energised by the July Revolution.

Its post-July positions, articulated in the August 2025 “Manifesto of New Bangladesh”, demand a new constitution, a Second Republic, and a ban on the Awami League until its leaders face trial for the alleged July massacre. Advocating PR and a constituent assembly election, the NCP appeals to those seeking a break from traditional politics, though its untested electoral strength and fringe stances risk alienating moderates.

The party’s focus on expat rights and anti-corruption resonates with younger voters but faces challenges from limited patronage-based grassroots networks.

2. The health of the economy

Bangladesh’s economic and business environment, shaped by a transitional government, offers foreign investors a mix of opportunity and risk.

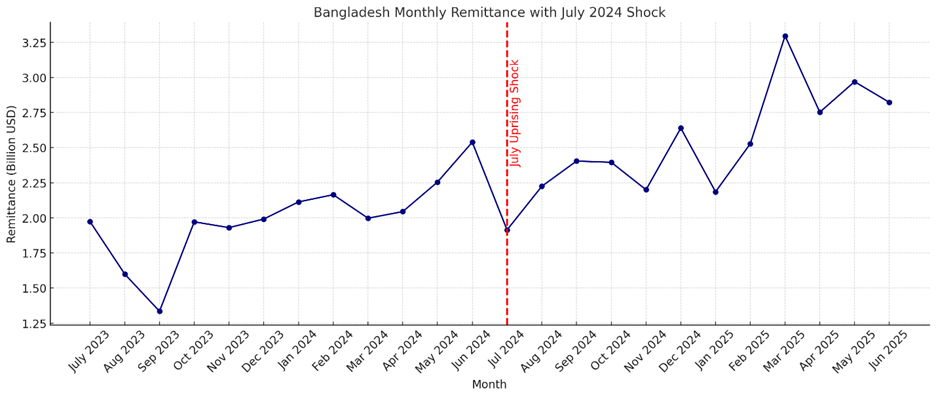

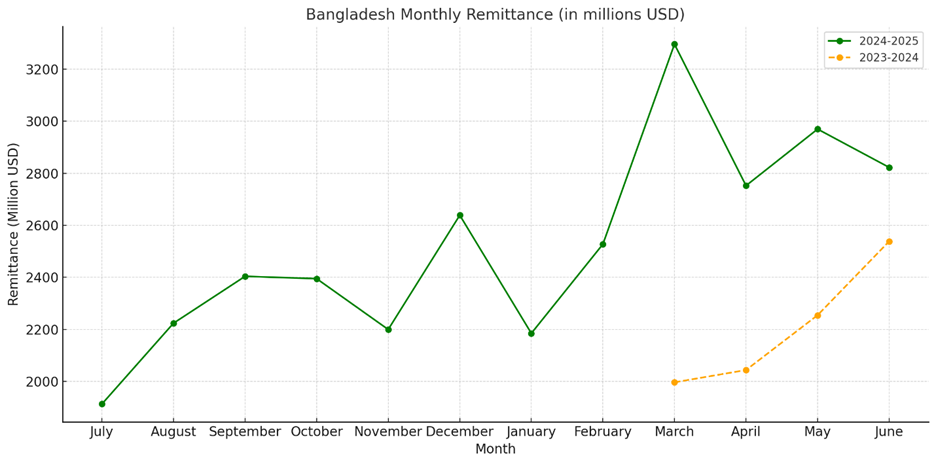

Economic performance has weakened, with FY25 GDP growth projected at 3.3% (down from 5.2% in FY24), driven by uprising-related disruptions, subdued investment, and a 20% surge in remittances (reaching $25 billion annually) that eased a prior hard-currency crunch.

Rising remittance inflows from expatriates signal growing optimism and increased confidence in the transition process.

Inflation, peaking at 11.7% in July 2024, fell to 8.48% by June 2025, supported by a stabilised taka, tighter monetary policy, and improved agricultural yields.

However, fiscal constraints persist, with a budget cut to curb deficits (4.3% of GDP in FY25) and low tax revenues (8.2% of GDP) limiting infrastructure spending.

The banking sector, crippled by systemic corruption under Sheikh Hasina’s 2009–2024 tenure, faces severe challenges, with non-performing loans exceeding 10% of total loans—one of Asia’s highest ratios.

Politically connected defaults, notably by S Alam Group (alleged to have embezzled $17 billion), eroded depositor confidence and prompted a 2025 Bank Resolution Ordinance replacing boards of 11 distressed lenders.

The IMF’s $1.3 billion loan in May 2025, tied to energy pricing and financial governance reforms, signals progress, but weak asset recovery and ongoing corruption allegations cloud credibility.

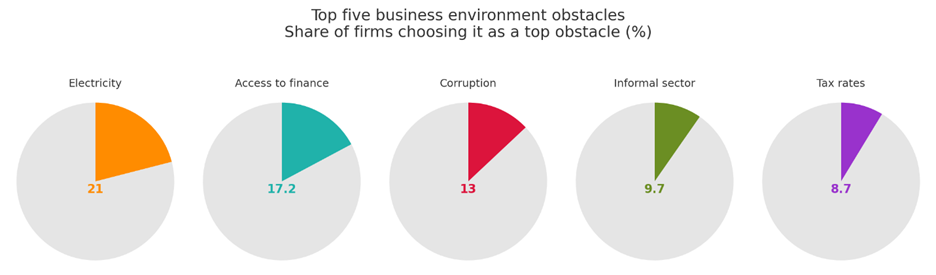

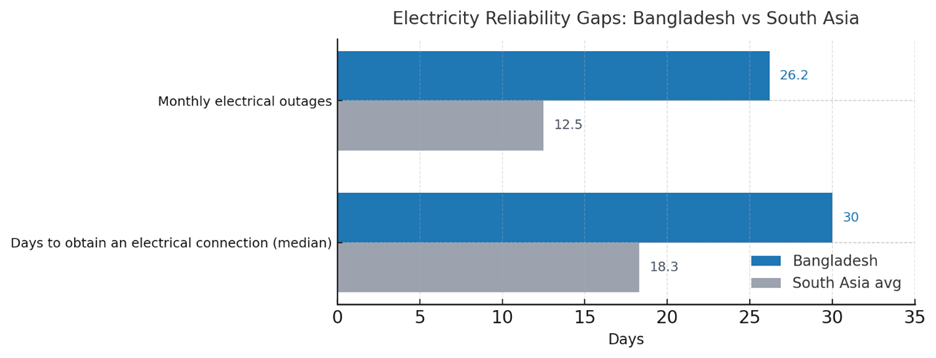

The business climate remains challenging, with Bangladesh ranking poorly on the World Bank’s Doing Business Index due to regulatory complexity, corruption (24/100 on Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index), and chronic power shortages.

Key sectors like ready-made garments (85% of exports) face risks from U.S. tariffs (20%) and post-2026 LDC graduation, yet pharmaceuticals and fintech offer growth, with the latter expected to be bolstered by Starlink’s recent rural connectivity rollout.

The interim government’s “Halal Economy 360” strategy aims to position Bangladesh as a $3 billion domestic halal hub, leveraging Malaysia’s expertise for export-orientated zones in food and cosmetics, attracting FDI. Trade competitiveness hinges on customs modernisation and GSP+ compliance with EU sustainability rules.

Infrastructure deficits, high borrowing costs, and informal sector competition stifle private sector growth, though Japan’s $1.06 billion package and India-U.S. trade war-driven interest in industrial parks signal opportunities in logistics and energy.

The 2026 election introduces uncertainty, with a potential BNP-led government favouring looser monetary policy, risking populist measures or policy reversals.

Investors should position cautiously in logistics, energy, and export infrastructure, leveraging joint ventures to hedge risks while capitalising on Bangladesh’s cost-competitive labour and strategic trade positioning. Governance reforms and asset recovery progress will be critical to restoring confidence and sustaining long-term growth.

3. Regional and international geopolitics

3.1 The Rohingya refugee question and the Civil War in Myanmar

Following the Arakan Army’s defeat of Myanmar’s military in northern Rakhine State by December 2024, Rohingya armed groups, representing the Muslim minority, unified in November 2024 to confront the Buddhist-majority Arakan Army.

By August 2025, the AA controls the entire 271-kilometre Myanmar-Bangladesh border and is poised to launch a monsoon offensive (September–October 2025) to capture Sittwe, the state capital, and Kyaukphyu, a strategic port central to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The AA’s estimated 40,000-strong force, bolstered by conscription of men (18–45) and women (18–25), has leveraged captured munitions and tactical advantages, such as using monsoon cloud cover to mitigate junta air strikes.

The AA, through its political wing, the United League of Arakan’s (ULA) December 2024 statement, emphasised a preference for political solutions over military escalation and invited foreign investment to develop Rakhine, signalling an intent to gain international legitimacy.

This shift followed years of violent infighting in Bangladesh’s refugee camps, where violence has since declined as these groups ramp up recruitment, framing their fight as a “jihad” against the Arakan Army, fuelled by its alleged abuses and anti-Rohingya rhetoric.

The Myanmar military had earlier forcibly recruited Rohingya men and collaborated with their armed groups to slow the Arakan Army’s advance, a surprising move given prior hostility.

The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) and other Rohingya factions, some backed by the junta, have engaged in limited operations against the AA, particularly in northern Rakhine.

However, their military impact is minimal, and their mobilisation, often using religious rhetoric, risks escalating ethnic tensions without altering the AA’s dominance.

Bangladesh’s government has cautiously engaged with the Arakan Army, which now controls Myanmar’s border with Bangladesh, but its security agencies’ backing of the Rohingya groups’ “unity” campaign threatens these talks.

This support, possibly aimed at pressuring the Arakan Army to accept refugee repatriation, risks escalating tensions and anti-Rohingya sentiment in Myanmar, jeopardising the return of nearly one million refugees.

Over 150,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh since 2024, joining 1.4 million refugees in Cox’s Bazar, where conditions are dire. Bangladesh faces challenges to curb the influence of Rohingya armed groups in the camps and strengthen dialogue with the Arakan Army.

The visit and hosting of a grand iftar with the UN secretary general last Ramadan (March 2025) was an ostentatious gesture without much real substance. The elected government in Bangladesh must take concrete and decisive steps to resolve several outstanding issues related to this crisis.

Rakhine’s Kyaukphyu port and oil/gas pipelines are critical to China’s BRI, connecting Yunnan province to the Indian Ocean. Beijing has adopted a dual strategy, intensifying support for the junta while engaging the AA to protect its investments. China’s backing of the junta’s elections and deployment of private security to Kyaukphyu reflect its prioritisation of stability.

However, AA control of key infrastructure could force Beijing to accommodate the group’s autonomy aspirations.

3.2 Indian foreign policy in Bangladesh is a train wreck

India’s diplomacy in Bangladesh since July 2024 has been a cascading failure, exposing New Delhi’s inability to anticipate the collapse of its key ally.

The “Monsoon Revolution” left India scrambling to preserve influence in a country vital to its regional security, situated next to the narrow, 27-kilometre-long “Chicken’s Neck” corridor—the sole land passage connecting New Delhi to the insurgency-prone, non-Hindu-majority northeastern states known as the “Seven Sisters.”

This diplomatic train wreck stems from India’s overreliance on Hasina, misreading Bangladesh’s domestic dynamics, and mishandling bilateral tensions.

Despite her authoritarian grip—marked by rigged elections in 2014, 2018, and 2024, and brutal crackdowns killing over 1,400 protesters in 2024—India doubled down on Hasina’s regime, lobbying the U.S. to soften criticism of her human rights abuses, citing fears of Islamist resurgence.

New Delhi’s unwavering support, including high-profile engagements like Hasina’s G20 visit in 2023, blinded it to the growing unrest, leaving India unprepared when she fled to Delhi on August 5, 2024.

BBC reported in August 2025 that BAL leaders have rented a party office in the neighbouring Indian state capital in Kolkata. The quiet consolidation of indicted Awami League fugitives poses a security threat to Bangladesh’s internal equilibrium.

Operating from a discreet “commercial office” under Indian tolerance, these former ministers and MPs are re-knitting the party’s fractured hierarchy, directing encrypted communications to dormant cadres at home, and tapping diaspora patronage to bankroll new campaigns.

Their sanctuary erodes Dhaka’s ability to enforce tribunal warrants, emboldens affiliated student and violent wings, and provides a launchpad for digital propaganda capable of catalysing street unrest ahead of the 2026 polls.

By outsourcing political strategising to foreign soil, the group invites covert leverage, sharpening the risk that bilateral frictions will be weaponised in Bangladesh’s domestic contest.

This combination of legal impunity, external sanctuary, and renewed internal organisation poses a meaningful risk of civil unrest that could, in turn, draw heightened bilateral tension between India and Bangladesh.

3.3 China and the United States compete for influence

Following Sheikh Hasina’s ouster, China has hosted multiple rounds of high-level visits in Beijing, inviting prominent Bangladeshi political leaders and student activists to meet with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials.

This is new.

China, the biggest economic partner with over $25 billion invested in Bangladesh’s infrastructure through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), seized the post-Hasina vacuum to deepen its influence.

Hasina’s hedged diplomacy, maintaining ties with both India and China, had kept Beijing’s ambitions in check. However, her refuge in India and deteriorating India-Bangladesh relations opened a window for China to strengthen ties with Yunus’s interim government.

Beijing’s $2.1 billion in investments, including a $400 million Mongla Port modernisation deal, signals a strategic push to secure maritime access and counter India’s regional dominance.

China’s engagement with local actors, including Islamist groups like Jamaat-e-Islami, suggests a calculated effort to cultivate political allies, leveraging Bangladesh’s $6 billion debt to Beijing for strategic gain.

The United States, meanwhile, has pivoted to prioritise transactional diplomacy and countering Chinese influence through the Indo-Pacific Strategy, while reducing emphasis on humanitarian aid, climate funding, and democratic reforms, potentially straining bilateral relations amid Bangladesh's political transition.

Washington’s earlier sanctions on Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion and visa restrictions on Awami League officials underscored its push for democratic reforms.

Post-uprising, the U.S. has engaged Yunus’s government to support institutional reforms, emphasising human rights and electoral integrity. The U.S. seeks to balance Chinese influence by maintaining economic leverage as Bangladesh’s largest export market while cautiously navigating China’s growing footprint.

The United States has also privately cautioned moderate Islamist groups such as Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) against empowering more extremist actors advocating strict Sharia implementation, including those associated with Hefazat-e-Islam.

Recent tariff disputes with India could create an opportunity for the United States to establish direct bilateral relations with countries like Bangladesh, which have historically fallen within India’s sphere of influence and were often seen through an Indian lens and indirectly managed by New Delhi.