This article is informed by confidential discussions with senior officials and diplomatic sources, and is part of GPD’s commitment to delivering ahead-of-the-curve insights.

We are currently preparing an in-depth report on Bangladesh's democratic transition. If you’d like deeper insight on this topic, contact us to request a complimentary copy of the full report.

A year after the Monsoon Revolution, which toppled long-time Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the initial excitement is fading in Bangladesh.

The opposition-backed interim government, led by Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus, has pledged to deliver reforms and ensure a level playing field for what would be the country’s first free and fair elections in 16 years. Yet party rivalries, institutional weakness, and external pressure threaten to derail the process.

The weight of history

The July–August 2024 uprising left at least 1,400 people dead in clashes with security forces, according to UN investigators. The interim government promised three things: justice for the massacre, institutional reform, and free elections.

On 5 August 2025, Yunus confirmed that polls will be held in February 2026, just before Ramadan.

Hasina’s 16-year rule hollowed out institutions. Elections under her watch often recorded turnouts as low as 20%, even with ballot-stuffing. Human rights groups documented 600 enforced disappearances and more than 500 extrajudicial killings between 2009 and 2024.

Corruption was systemic: an estimated $240 billion was siphoned abroad during her tenure. The regime’s collapse left a civil–military bureaucracy compromised, police demoralised, and public trust in government institutions near zero.

Electoral uncertainty

For Yunus, legitimacy rests on fragile ground. He briefly considered resignation in mid-2025, frustrated by coalition infighting, before striking a deal with BNP’s exiled leader Tarique Rahman in London to fix the election date.

During Hasina's tenure, elections were managed through state violence. With that monopoly now broken and security forces weakened, the risk of inter- and intra-party clashes is high.

To preserve continuity and shield the revolutionaries, the opposition parties adopted the July Charter, which sets out 84 reforms across constitutional governance, electoral integrity, judicial independence, and anti-corruption enforcement.

Core provisions include limiting prime ministerial terms, strengthening caretaker government mechanisms, and restructuring the judiciary and police.

But disputes over implementation—whether by referendum, parliament, or a transitional assembly—have stalled progress.

Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) resists granting the Charter supra-constitutional status, arguing it undermines the republic’s legal framework.

Meanwhile, the student-led National Citizen Party (NCP) and Islamist parties demand the Charter be binding before elections. Even if polls proceed, the risk of boycotts and partial delegitimisation remains high.

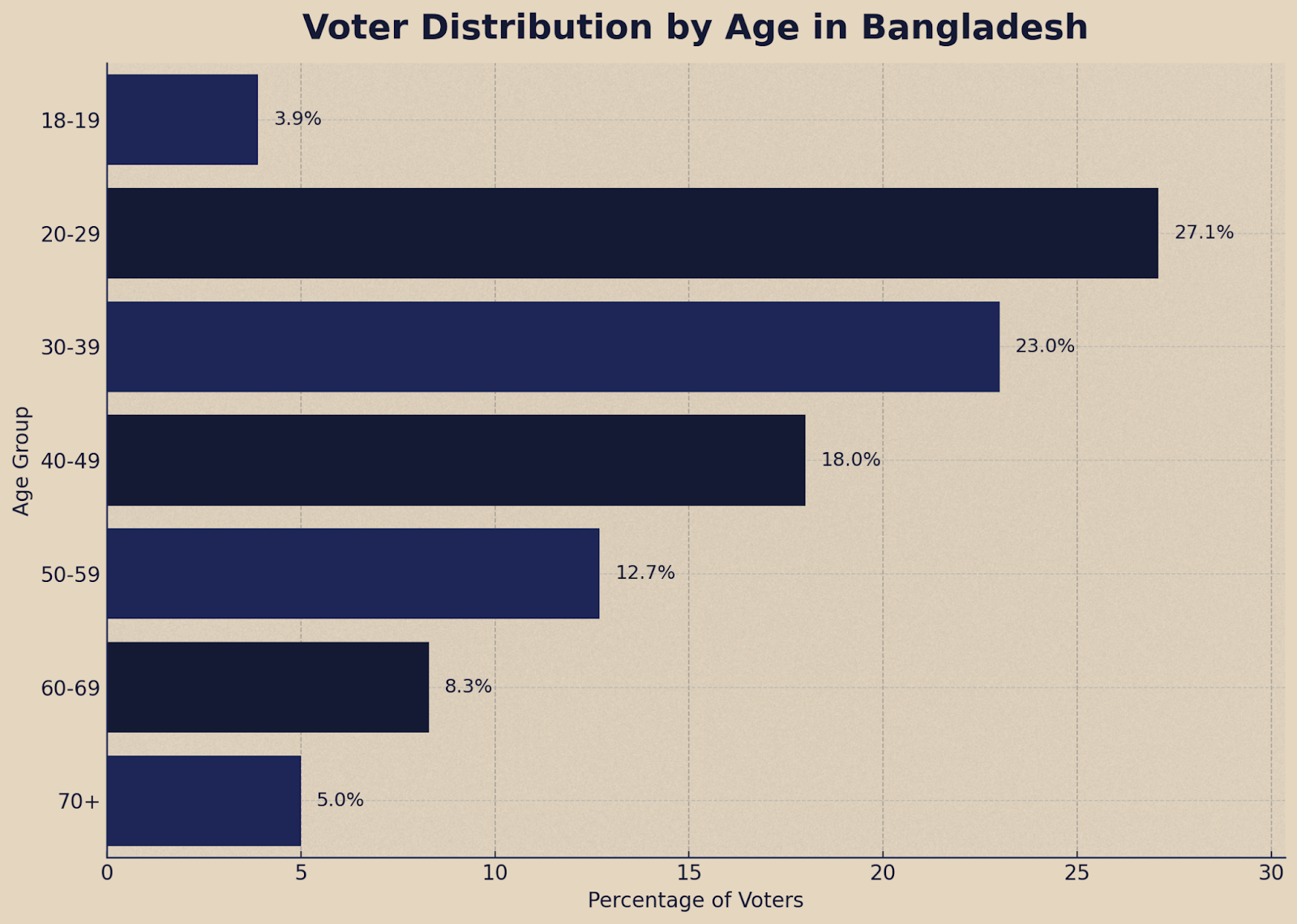

Capacity is another constraint. The bureaucracy has not run a credible election since 2008 yet must now administer voting for 115 million citizens across more than 40,000 polling stations.

Many of these voters are Gen Z or Millenials who have not yet had a chance to cast their votes in any election, and are eager to have their voices heard and enable change.

Political dynamics

Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)

With the Awami League dismantled, BNP has emerged as the dominant political force and is widely perceived as the next governing party.

Its programme emphasises democratic restoration, depoliticisation of institutions, and transparent governance. Promises include judicial reform, an empowered anti-corruption commission, and decentralisation. The BNP has pledged to form a unity government if victorious.

The party rejects proportional representation in favour of a reformed first-past-the-post system, aiming to avoid fragmentation. Its long-term vision includes a bicameral legislature and term limits for prime ministers. These proposals open opportunities in civic tech, governance digitisation, and human rights infrastructure.

Tarique Rahman, BNP’s de facto leader, remains in exile in London. Elements of the military still resist his return, but public pressure may force accommodation. His ability to contest will shape the credibility of the election.

Awami League (BAL)

From exile in Delhi, Hasina is orchestrating a comeback bid, directing loyalists via encrypted channels and diaspora networks.

“Operation Devil Hunt,” a nationwide crackdown, has jailed more than 11,000 supporters and stripped the party of legal status. Hasina faces trial in absentia for crimes against humanity, yet she bets on voter fatigue and Indian diplomatic cover to secure re-entry.

In practice, the odds of BAL’s rehabilitation are low.

With its machinery dismantled, leaders incarcerated, and public opinion hostile, the party risks fading into irrelevance unless a future government embraces reconciliation—politically toxic for now.

Jamaat-e-Islami (JI)

Reinstated in June 2025, JI is positioning itself as an “Islamist left” force, blending religious conservatism with social justice and anti-corruption themes.

Its support base remains limited—conservative youth, madrasa networks, and 4–10% of the electorate—but its demand for proportional representation and constitutional reform gives it leverage.

Its controversial role in the 1971 Liberation War continues to hinder broader acceptance.

Jatiya Party (JP)

Traditionally allied with BAL, JP commands 5–7% of the vote in northern districts.

Post-2024, it has sought to reinvent itself as a moderate force supporting early elections and proportional representation.

If BAL loyalists run under its banner, JP could become the main opposition, inheriting parts of BAL’s base.

National Citizen Party (NCP)

Formed by student leaders of the Monsoon Revolution, NCP appeals to young, reform-minded voters.

Its manifesto calls for a new constitution, a Second Republic, and a ban on BAL until trials conclude. Its estimated 5% voter base is small but vocal, especially in urban areas and the diaspora.

Without alliances, however, its impact is likely to be marginal.

Where do the major parties stand regarding the reform proposals?

Scenario Analysis

Scenario 1: Orderly Democratic Transition

Under this scenario, Bangladesh manages a peaceful, credible, participatory election in February 2026, resulting in a widely accepted outcome and a stable transfer of power to an elected government.

The probability of this orderly transition is bolstered by the interim government’s reform efforts, as well as historical precedents where neutral caretakers delivered fair elections (e.g., 1991, 1996, and 2001).

The current government is currently planning the procurement of 40,000 police body-worn cameras and drones, the deployment of a record number of security personnel, the queuing of a European Union pre-election assessment, the updating of voter rolls and the ensuring of neutral election oversight.

However, this scenario assumes no major relapses into the zero-sum politics or violence that have marred past polls.

At the same time, inclusion risks remain material, with continuing controversy over Awami League’s suspension and broader political resistance to reforms, which rationally caps the likelihood below 50%.

An orderly transition would significantly lower Bangladesh’s political risk profile.

Investors who have so far adopted a wait-and-see approach would regain confidence. Business leaders note that investment has stalled amid uncertainty, and many are waiting for a newly elected government.

With stability restored, Bangladesh could see an inflow in FDI and financing. The end of protracted turmoil would likely ease the political risk premium on Bangladesh’s assets, lowering borrowing costs and attracting capital back into equities and projects.

Scenario 2: Disputed Outcome

The election produces a contested result, sparking a political crisis. Outcomes include protests, legal challenges, and violent stalemate without clear legitimacy.

Bangladesh has faced similar episodes. In 1996 and 2014, opposition parties rejected results, leading to unrest, boycotts, and repeat polls.

In 2026, despite caretaker oversight, entrenched patron-client networks could compromise neutrality, especially as officials anticipate a BNP-led government. BNP has warned of instability if timelines slip and institutional distrust persists.

Reforms may not overcome weak law enforcement or rivalries within the National Unity Commission. A close result could quickly produce allegations of fraud or bias.

Whether BNP wins narrowly or a third-force coalition surprises, disputes may trigger protests, strikes, and violent confrontations reminiscent of 2014.

If neither side concedes, Bangladesh risks protracted deadlock requiring military or international mediation. An extended caretaker tenure through legal action, presidential decree, or paralysis would echo the 2007 precedent, prolonging uncertainty.

A crisis would disrupt business operations. Strikes and blockades could halt domestic transport and exports. The garment sector—worth $45 billion—would be particularly exposed, as seen in 2013 when strikes delayed shipments. A 2025 survey found 75% of business leaders citing political instability as the top risk.

Factory walkouts, supply-chain rerouting, and export delays would follow. Global retailers may shift sourcing, denting export earnings. Financial investors would reallocate to safer markets.

Regionally, Awami League exiles in India may exploit the crisis to fuel instability. China and other partners could delay initiatives, including Belt and Road projects, until stability returns, slowing connectivity plans. A disputed outcome would cement Bangladesh’s image as politically volatile, discouraging long-term investment.

Scenario 3: Security Breakdown or Emergency Measures

The transition collapses into widespread violence, prompting emergency rule or even military intervention.

Polarisation, reform failures, and breakdown of unity dialogues could converge with triggers such as communal clashes or insurgent violence. Yunus himself has hinted at resignation over stalled reforms. The February 2026 date has already shifted multiple times, reflecting elite fragmentation and fuelling doubts about whether polls will occur.

Scenario 3 anticipates violent clashes between rival activists, targeting of minorities, and opportunistic violence by the banned Awami League operating from India. Authorities may suspend the vote under emergency law. Curfews, army deployment, constitutional suspension, media restrictions, and mass arrests would follow. In the worst case, the military reconfigures the caretaker into a martial-law regime.

This scenario renders Bangladesh temporarily unviable for most operators. Curfews and violence could shut factories in Dhaka and Chittagong, force expatriate evacuations, and trigger order cancellations under force majeure. The apparel sector and allied industries would be paralysed.

Financially, confidence would collapse: taka depreciation, capital flight, volatile markets, rising bond yields, and possible rating downgrades.

Public projects—ports, power plants, transit corridors—would stall. Contractors face payment delays, while government-linked firms operate in limbo. Insurance claims, premiums, and war-risk surcharges would spike. Lenders may invoke political-risk clauses, delaying disbursements or accelerating repayments.

Even after normalisation, reputational damage would divert FDI to safer regional competitors.

India could face refugee inflows and a security vacuum in its Northeast. The Rohingya crisis would worsen if Bangladeshi governance collapses. Chinese and Japanese investments in ports and power plants would be jeopardised, straining bilateral ties.

Outlook

The February 2026 election is both feasible and fragile. The base case is an orderly transition under BNP, supported by interim safeguards and public appetite for reform.

Yet institutional weakness and elite uncertainty cap confidence. A relapse into repression or prolonged interim rule cannot be discounted.

Bangladesh’s fundamentals still argue for opportunity. But unlocking it depends on executing a clean vote at speed—something the country has not achieved in over a decade.

This article is free to read and is part of our commitment to delivering ahead-of-the-curve insights.

Subscribers on our Intelligence and Enterprise plans access confidential reporting like this on a regular basis, as well as business intelligence, geopolitical forecasts and strategic insights not available elsewhere.

If you’d like deeper insight on this topic, consider subscribing to one of our paid plans today. Your subscription directly supports independent research in the world’s most complex regions.

We are currently running early bird pricing for new subscribers. Click the button below to get 60% off the first 3 months of your Intelligence subscription.