We are currently running early bird pricing for new subscribers. Click the button below to get 60% off the first 3 months of your Intelligence+ subscription.

With growing political instability in western Libya, there is a clear sense that the status quo is shifting, triggering an intensified struggle over the country’s vast natural wealth.

A political stalemate between the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli and the rival Government of National Stability (GNS) in Benghazi for the past few years has incentivised Libyan political, security, and criminal groups to focus on profiting from the country’s lucrative oil industry.

However, rising instability in western Libya, increased international interest in the oil sector and the normalization of relations with eastern Libyan actors are now significantly disrupting that balance.

Politicians, criminal networks, security forces, regulatory bodies, financial institutions, and international players are all becoming increasingly entangled in the growing fight to control Libya’s resources.

Networks of enrichment

Libya’s main actors have been able to build a complicated but lucrative system that allows them to benefit from multiple places in both the financial and oil sectors.

The system operates roughly as follows.

First, the National Oil Corporation (NOC) and its subsidiary extraction companies drill for and collect crude oil. Since Libya lacks sufficient refining capacity to convert this crude into usable fuel, the NOC and its export subsidiaries trade crude oil for processed fuel from other countries.

Fuel requirements are set by state-owned entities like the General Electric Company of Libya (GECOL) as well as private service companies, which often provide artificially inflated figures to justify increased fuel imports.

During this “oil for fuel” exchange, numbers are manipulated at several stages. Exporters likely misreport the volume of crude shipped, while importers likely underreport the amount of refined fuel received, allowing these groups to slowly skim off the top.

Once the refined fuel arrives in Libya, criminal groups frequently siphon it off or steal it from delivery trucks en route to fuel stations.

The inflated fuel demands from organisations like GECOL provide cover for importers to further manipulate figures, while also ensuring a steady supply of fuel that criminal networks can divert and sell at inflated prices.

Meanwhile, revenues from official NOC transactions are transferred to the Central Bank of Libya (CBL), which allocates funds to government employees and institutions under both rival administrations.

As both governments continue to ramp up spending, the CBL is compelled to inject more funds into state bodies—many of which use the money for political patronage or personal enrichment.

Tight budget

Libya’s budget is almost fully spent by the state, making the economy highly susceptible to changes in oil prices or damages to oil output.

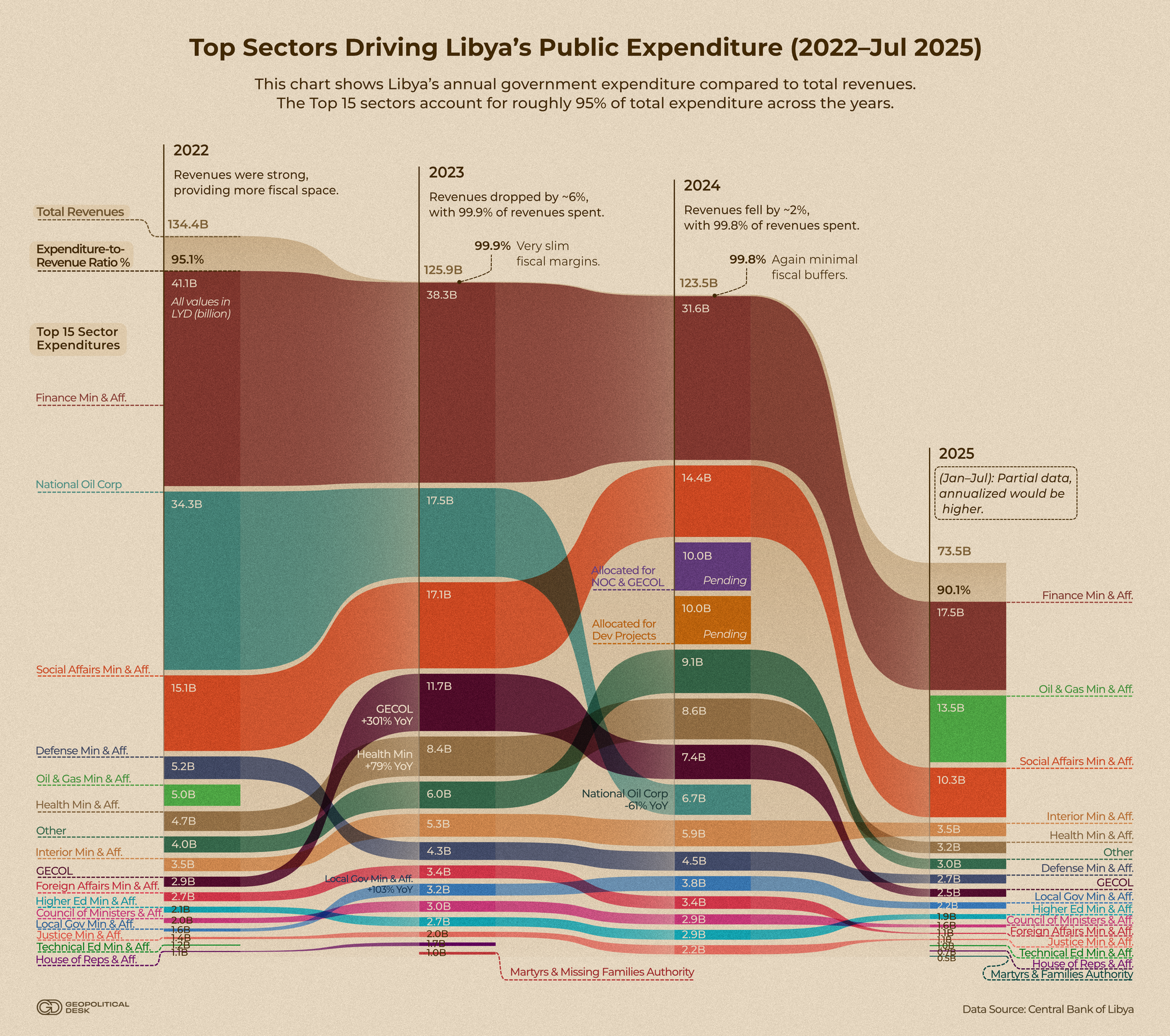

In 2023 and 2024, the GNU spent around 99.9% of its entire budget. Data published by the Central Bank of Libya also does not count for the spending conducted by the rival Government of National Stability in Benghazi.

As shown in the graph below, there is also an ever increasing amount of money moving away from the National Oil Corporation and toward other ministries providing social services.

Since almost all of Libyan state revenue comes from the oil sector, the ever decreasing budget for the NOC is concerning. This is paired with increased budgets for the Ministry of Social Affairs and the GECOL, with the latter using that money to import fuel that is increasingly used for smuggling.

In many countries, governments sometimes spend more than they bring in—this is called deficit spending. It works when the economy is growing fast enough to keep up with rising debt.

In Libya, however, this approach doesn’t work. The country’s economy is heavily reliant on oil prices, making public debt accumulation risky because its finances can’t absorb the shockwaves from global oil market swings.

As a result, Libya has stayed away from international debt markets, but it has nonetheless accrued obligations to Central Bank. The CBL covers these fiscal advances through monetary financing, which in turn fuels inflation and puts pressure on the national currency.